Успенский и Богоевленский соборы - доминанта города

Славен город Кострома

(RU)

Доведись пора вечерняя,

Не дойдешь - сойдешь с ума!

Хороша наша губерния,

Славен город Кострома

«Славен город Кострома», — с улыбкой повторяют и костромичи, и туристы с детства запомнившуюся строчку из «Коробейников» Н. А. Некрасова. Тысячу лет назад спустились сюда с верховьев Волги ладьи первых поселенцев-славян, а в 1152 г., по сведениям историка В. Н. Татищева, князь Юрий Долгорукий обнес растущее селение крепостной стеной. Так возник город. Его многовековая история наглядно представлена в экспозиции местного историко-архитектурного музея-заповедника. Он размещен в древнем, основанном в последней трети XIII в. Ипатьевском монастыре, каменные сооружения которого XVI—XVII вв. являются превосходным художественным ансамблем. В этом монастыре найдена знаменитая Ипатьевская летопись, воссоздающая прошлое нашей Родины. Летописцы повествуют, как костромской князь Василий Ярославович, младший брат Александра Невского, заняв в 1272 г. великокняжеский престол, не пожелал покидать Кострому. Да и позднее Кострома не растеряла своей славы. В XVII в. по численности населения она — третий, после Москвы и Ярославля, город России, крупный торговый центр. Своеобразным свидетельством былого процветания богатого костромского купечества служат торговые ряды конца XVIII — начала XIX в. Любителям старины знакомы ряды в Суздале. Костромские — значительно больше, соразмернее. К созданию их «приложили руку» и петербуржец В. П. Стасов, и костромич П. И. Фурсов. П. И. Фурсову, выведенному в романе А. Ф. Писемского «Люди сороковых годов», принадлежат лучшие, пожалуй, костромские здания XIX в.: дом соборного притча на ул. Чайковского, каланча, гауптвахта. Некоторые памятники древней архитектуры Костромы, к сожалению, погибли во время опустошительных пожаров.

В средние века город страдал и от вражеских нападений. К. Ф. Рылеевым и М. И. Глинкой воспет подвиг костромского крестьянина Ивана Сусанина. Сейчас монумент мужественному патриоту возвышается в центре Костромы.

Кострома гордится и одним из талантливейших отечественных живописцев XVII в. Гурием Никитиным, и первым национальным актером Федором Волковым, тоже местным уроженцем, и безвестными и искусными древоделами-плотниками, резчиками по дереву: образцы их высокого мастерства собраны ныне в музее деревянного зодчества у ограды Ипатьевского монастыря. Туда свезены такие уникальные сооружения, как храм XVI в. из села Холм Галичского района, церковь на сваях XVII в. из села Спас Костромского района, старинные избы, ветряные мельницы, баньки и т. д. Впрочем, и прямо на улицах самого города сохранились оригинальные деревянные дома XVIII— начала XIX в.: ведь каменными зданиями Кострома усиленно застраивается лишь в течение двух последних столетий, с появлением полотняных мануфактур. Мануфактуры, первоначально занимавшие центральные улицы, позднее переместились на окраины, в фабричный район, поэтому последующее превращение Костромы в крупнейший центр российской льняной промышленности не исказило исторически сложившегося облика города. В настоящее время к текстильным предприятиям добавились машиностроительные заводы, однако и они располагаются вдали от центра, преимущественно на правом берегу Волги. Обе части города недавно соединены многопролетным пешеходным мостом.

Многочисленный отряд костромского пролетариата активно участвовал в рабочем движении России, а первый социал-демократический кружок здесь основан в 1891 г. ссыльным путиловским рабочим В. Буяновым. С Костромой связана деятельность выдающегося революционера-демократа П. Г. Зайчневского, Н. Флеровского (В. В. Берви), автора книги «Положение рабочего класса в России», а позднее — Я. М. Свердлова, Н. Г. Полетаева, М. В. Фрунзе, А. М. Стопани, Н. Р. Шагова.

В Костроме живет сейчас около 250 тысяч человек. Город расширился, застроился многоэтажными зданиями, благоустроился. Но градостроители бережно сберегли все ценное и запомнившееся в архитектуре и планировке Костромы, в том числе и ансамбль центральной площади.

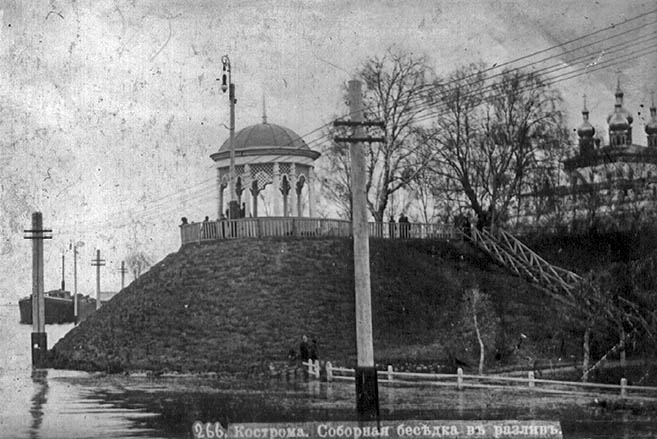

А. Н. Островский, тесно связанный с Костромой, часто любовавшийся окрестностями из беседки на городском валу над широкой Волгой (она до сих пор именуется «беседкой Островского»), отмечал, что его привлекает своеобразный, радостный вид костромских улочек и набережной. «Кострома — это город-улыбка»,— определил в 20-х гг. Демьян Бедный и свою поэму «Кострома» закончил словами: «Шутка шуткой, а вот я возьму и махну навсегда в Кострому».

Russian town Kostroma

(EN)Russian artistic and cultural traditions were cultivated in the Kostroma region for centuries. Many of the region’s unique and highly artistic architectural monuments have been preserved, as well as, examples of skilled metal forging and wood carving.

A. N. Ostrovsky, N. A. Nekrasov, B. M. Kustodiev and other prominent men in the world of arts and letters were frequent visitors in Kostroma. And A. F. Pysemsky lived here for many years.

***Kostroma was founded in the middle of the 12th century. At that time Russia waged a struggle with the Volga-Kamsk Bulgaria for trade routes along the Volga. Many settlements along the Volga were strengthened and forts were built in Kostroma and other towns.

According to a legend, Prince Juri Dolgoruki came here with his forces to protect merchants and other traders from marauders, and founded the town.

In the middle of the 13th century Kostroma became the seat of an independent principality, but in the first half of the 14th century it was incorporated into the Moscow Principality. Kostroma was burned-down and plundered many times during foreign invasions and wars between the principalities. That is why earlier buildings have not been preserved. All that has survived is the ikon of the Fyodorov Virgin, 13th century, (now in the Resurrection church on-the-Debre, in Kostroma), the 14th century St. Nicolas ikon (the Russian Museum, Leningrad), and a few smaller objects found during archeological excavations in the town. The study of these objects has shown that even in those distant times there were talented craftsmen who helped create local artistic traditions that are still alive today.

Due to its favorable location and lively trade in the 15th-16th centuries, Kostroma became a major crafts and trade center. By the end of the 16th and the first half of the 17th century it had grown into one of Russia’s major towns.

Wood was the main building material in Kostroma, at the time, because the town was situated among forests. But the town was constantly plagued by large-scale fires. And after the fire of 1413, the town’s Kremlin (fort) was built anew on Volga’s higher bank. A detailed description of it has come down to our time. The fort had 14 towers and 3 gates. Its oak walls were surrounded by moats.

Of course, it is hard to reconstruct in full the picture of old Kostroma. But according to 17th century manuscripts and a few remaining drawings, it was a wooden town with many marquee churches, closely standing houses, uneven streets and wooden bridges across ditches and streams.

By the middle of the 17th century Kostroma became a major trade and cultural center of the Moscow state. The town’s builders, ikon painters, silversmiths, weavers, blacksmiths and leather craftsmen were known throughout the land. Its lathergoods were exported abroad and its linen, scales and locks were known far and wide. Kostroma stone — masons were invited to build palaces and cathedrals in the capital and other towns. Especially well-known were the town’s painters, who were invited to paint the walls in the cathedrals of Moscow, Yaroslavl, Peres-1 avl-Zalessky and Suzdal.

Among the well know 17th century architectural monuments in the town are the Trinity Cathedral of the Ipatiev monastery, the Resurrection church on-the-Debre, The St. John the Divine church in the Ipatiev (now Labot) district, the Ilyinsk and the Spas-Transfiguration churches and the Ascension church on Melnychni St.

When, in 1778, Kostroma became a provincial seat, the construction of administrative buildings was begun. The building was conducted according to a general plan approved in 1784. The center of the town was devastated by fire in 1773, and this greatly aided builders in implementing their successful reconstruction plan.

It took nearly a half a century to create the central ensemble. Many architects worked on the project among them such well known ones as S. Vorotilov, who was employed at the end of the 18th century and P. Fursov, who was appointed the provincial architect from 1822 to 1831.

***The historical and architectural museum complex of the Ipatiev Monastery is the town’s major attraction. It was built in the 13th century as a fort at the spot where the Kostroma river flows into the Volga. The monastery’s elaborate complex of buildings includes structures dating from the end of the 16th to the end of the 19th centuries.

In the 16th century, thanks to the a large endowment from the Godunov family, the Ipatiev monastery became one of the largest feudal church holdings. Beginning with the 17th century the monastery began to be patronized by the new Tzarist family — the Romanovs.

The monastery’s sacristy housed many treasures and the library many unique manuscripts and first printed books among them the famous chronicle a copy of one of the most ancient codes of the 9th-12th century Kiev Russia—the “Tale of the Temporal Years”.

The oldest part of the monastery — the old town-dates back to the monastery’s founding. The stone walls and towers were built at the end of the 16th century, in place of the wooden ones, and were strengthened in the 17th century. In the 1740-ties the so-called “New town” was built along the fort’s western wall.

The monastery walls were surrounded by moats, but they were filled in in the 18th century, when the fort lost its strategic significance. In the center of the ensemble is the Trinity Cathedral. This stone structure was first built in 1558, but in 1649, it was blown up and reconstructed in 1652.

Of great artistic value are the frescos in the cathedral. They were painted in 1685, by a group of craftsmen working under the outstanding painters Guri Nikitin and Syla Savin. These frescos are the best examples of their work- The colors of the frescos are rich, the contours are graceful but firm, there are numerous details and the portraits are very down-to-earth. The architecture of the depicted palaces and halls is very interesting. On completing the fresco^ the artists wrote, as if speaking to future generations: “Artistic imagination and spirital fulfilment forever. Amin”.

The cathedral’s five-tier gilded ikonostasis was installed in 1756-1758. It was executed by a group of wood carvers from the Bolshye Soli settlement of the Kostroma province. They worked under the craftsmen Pyotr Zolotarev and Makar Bykov. Of special value are the ikons on the three upper tiers.

West of the cathedral, on the main square, stands the bell tower. In the 17th century it had 19 bells and also a clock with chimes. In 1852, the tower’s wooden stairs were replaced by stone ones. Part of the arches on its sou-thern side were bricked in and a gallery was added in the west.

Throughout the monastery there are many administrative structures and living quarters— from the modest monk’s cells to the splendid bishop’s palace. These building were often reconstructed to accord with the tastes of the ruling bishop or architectural fashion.

Near the monastery an open air museum of old wooden structures is being set up. Its purpose is to demonstrate folk building of secular and civil structures in the Kostroma villages, and the way the inhabitants lived. Kostroma carpenters were well known, especially those from the Galich and the So-ligalich counties that abounded in forests.

The museum began to be created in 1955, when work was under way to clear the Kostroma low-lands that were to be flooded by the dam of the Gorki Power Station. The Transfiguration church from the Spas-Vezhy village, an excellent example of 17th century Russian wood architecture, and a number of bath-houses from the Zharki village were moved then.

Most of the buildings in this open-air museum stand outside the monastery’s territory. Of special interest is the Our Lady cathedral-church from the Kholm village of the Galich district. It was built in 1552, and is the oldest standing structure in the Kostroma region. The carpenters who built it were great craftsmen.

Most of the wooden structures stand on the southern side of the monastery protected by a dam. Among them is the 18th century church from Fominskoye village. It is very characteristic of the church style of those times with a small belfry built a top the refectory. Then there is the small chapel that used to stand at the cross-roads in the Chukh-lomsk district. It was built in 1860-ties but looks very much like the houses described in ancient Russian fairytales.

Many peasant houses, flour-mills and other buildings are now undergoing reconstruction. Among them are houses with very curious balconies, window frames and shutters, as well as metal-cased chimneys and wrought iron dragons and verdure on the wooden gates. Standing on this bank of the Volga it is hard to grasp that on the other side stands a large industrial district of a contemporary town.

Durant des siècles, les traditions artistiques, donnant une idée complète de l’art et de la culture russes, se développaient dans la région de Kostroma. De magnifiques œuvres d’architecture, des spécimens de fin écrouissage, de ciselure sur bois s’y sont conservés.

Kostroma est liée au nom de beaucoup de représentants de la culture: A. Pissemski y a vécu pendant longtemps, A. Ostrovski, N. Nékrassov, B. Koustodiev l’ont visitée plus d’une fois.

***

Gazebo et du Kremlin

La fondation de Kostroma date du milieu du XIIe siècle. A cette époque, la Russie engagea la lutte contre les Bulgares de la Volga pour la domination commerciale de ce fleuve. Tout cela nécessitait le renforcement des cités riveraines; à Kostroma, comme ailleurs, on construit une forteresse.

La légende de la fondation de Kostroma nous rappelle que Youri Dolgorouki, venu avec sa troupe pour défendre les marchands contre les incursions des brigands, fut le fondateur de la ville.

Au milieu du XIIIe siècle, Kostroma devient chef-lieu de principauté apanagée; dès la première moitié XIVe siècle, elle est rattachée à la principauté de Moscou. La ville qui fut à maintes reprises détruite, lors des guerres intestines, n’a pas conservé d’anciens monuments. Se sont conservées les seules icônes de la Sainte-Vierge Fédorovskaïa datant du XIIIe siècle (église de la Résurrection “na Débré” a Kostroma) et “St-Nicolas et ses actes” datant du XIVe siècle (Musée russe à Léningrad), ainsi que quelques objets trouvés sur le territoire de la ville lors des fouilles archéologiques. Ces trouvailles, bien que peu nombreuses, nous permettent de parler des maîtres talentueux de Kostroma de ces temps reculés qui créèrent des traditions artistiques durables.

Grâce à sa position favorable — elle est située sur une voie commerciale—Kostroma devient, aux XVe — XVIe siècles, un centre artisanal et commercial important, et, à la fin du XVIe et dans la première moitié du XVIIe siècle, elle est déjà parmi les plus grandes villes de la Russie.

La ville, entourée de forêts, fut d’abord construite en bois. Des incendies dévastateurs très fréquents dévoraient ses constructions. Après l’incendie de 1413, on bâtit le kremlin sur le lieu le plus élevé de la rive de la Volga. Une description détaillée de ce kremlin nous est parvenus. Il possédait quatorze tours et trois portes fortifiées. Ses murs en chêne furent ceinturés de fosses.

Aujourd’hui il est difficile d’avoir une idée claire du panorama de l’ancienne Kostroma. Des cadastres datant du XVIIe siècle et des dessins peu nombreux nous permettent d’évoquer la bizzare silhouette de la ville en bois, ses nombreuses églises pyramidales qui se dressaient au-dessus des constructions paroissiales, ses rues, ses ponts.

Vers le milieu du XVIIe siècle, Kostroma, important centre économique, devient un grand foyer de culture en Moscovie. Ses architectes, ses peintres d’icônes, ses peaussiers, ses forgerons, ses maîtres argentiers et tes-serands étaient hautement appréciés. Les toiles, les balances, les cadenas étaient connus hors de ses limites. On invita les architectes de Kostroma à participer à la construction des palais et des cathédrales dans la capitale et dans beaucoup d’autres villes.

Les peintres d’icônes de Kostroma jouissaient d’une popularité exceptionnelle. Ils couvraient les murs des cathédrales’ de Moscou, de Yaroslavl, de Péréslavl-Zalesski, de Souzdal d’une magnifique peinture.

La cathédrale de la Trinité du Monastère St-Ipate, l’église de la Résurrection “na Débré”, l’église St-Jean Chrysostome, qui se trouve dans le faubourg Ipatiévska'ïa (aujourd’hui Troudovaïa), l’église du prophète Elie, l’èglise de la Transfiguration du St-Sauveur au-dejà de la Volga, l’église de l’Ascension dans la ruelle Mielnitchny, sont des monuments architecturaux du XIIe siècle très connus.

La construction des bâtiments s’effectuait d’après le plan général, élaboré en 1784. La destruction du centre de la ville par l’incendie de 1773 permit de réaliser de nouveaux plans d’urbanisme.

Le centre de la ville fut réaménagé pendant près d’un demi-siècle; divers architectes prirent part à sa création, dont S. Vorotilov, qui travaillait à la fin du XVIIIe siècle et P. Foursov, architecte de gouvernement dans les années 1822—1831.

***Le Musée d’Histoire de l’architecture du monastère St-Ipate présente un grand intérêt.

Ce monastère, fondé au XIIIe siècle près du confluent de la Kostroma et de la Volga, est une forteresse à plusieurs constructions datant de diverses époques: de la fin du XVIe siècle au dernier quart du XIXe siècle.

Au XVIe siècle, grâce à de reches dons (des Godounov, principalement), le monastère St-Ipate prend place parmi les plus importantes possessions de l’église. Dès le début du XVIIe siècle, il est placé sous les auspices de la nouvelle dynastie des Romanov.

De grandes richesses artistiques sont conservées dans la sacristie du monastère; on peut trouver dans sa biblithéque les manuscrits uniques et les premiers livres imprimés, dont une copie de l’illustre “Chronique de l’ancien temps”, un des plus anciens corps de la Russie kiévienne des IXe — XIIe siècles.

La “vieille ville”, la partie du monastère la plus ancienne, existe depuis sa fondation. Les murs en pierre qui avaient remplacé, à la fin du XVIe siècle, ceux en bois, furent élevés au XVIIe siècle. Dans les années 40 du XVIIe siècle, on construit, le long de la muraille de la vieille ville ce que l’on appelle la ville Neuve. Autour des murs on creusa des fossés, comblés au XVIIIe siècle, époque où le monastère perdit son importance.

La cathédrale de la Trinité occupe la place centrale de l’ensemble. La première construction de la cathédrale en pierre date de 1558. Au début de 1649, elle fut détruite sous l’effet d’une explosion et reconstruite en 1652.

La peinture mural de la cathédrale, monument remarquable de l’ancien art, est réalisée en 1685 par un groupe de peintres d’icônes de Kostroma sous la direction de Gouri Nikitine et Sila Savine, maîtres bien connus au XVIIe siècle. La peinture de la cathédrale de la Trinité du monastère St-Ipate est une de leurs meilleures réalisations. La diversité des couleurs, la finesse des formes, la composition contenant une multitude de détails de genre, la caractéristique des personnages, tout cela est plein de vie. L’ornement des térèmes et chambres est fort intéressant.

Une iconostase dorée à cinq rangées, spécimen de l’art du XVIIe siècle, fut placée dans la cathédrale en 1756—58. Elle est due à un groupe de sculpteurs du village Bolchié Soli qui alors faisait partie du gouvernement de Kostroma. Les maîtres-sculpteurs Piotr Zol-otarev et Makar Bykov ont dirigé ce travail. Les icônes des trois rangées supérieures ont une grande valeur artistique.

Le clocher se trouve sur la place centrale à l’ouest de la cathédrale. Au XVIIe siècle il possédait dix-neuf petites et grandes cloches, ainsi qu’une horloge à sonnerie. En 1852, les escaliers en bois furent remplacés par ceux en pierre; on aborda la construction des arcs, une galerie fut ajoutée à la paroi ouest du clocher.

Diverses constructions longent les murs du monastère, depuis le simple corps des cellules des moines jusqu’au corps majestueux de l’episcopat. Ce dernier fut reconstruit à maintes reprises selon les goûts des évêques et conformément aux nouvelles tendances de l’architecture.

On inaugure, près des murs monastiques, le Musée de la charpente populaire afin de conserver des monuments civils et culturels uniques de l’architecture populaire qui nous initient aux us et coutumes des villages de la région de Kostroma. La maîtrise de ses charpentiers jouissait depuis longtemps d’une grande popularité. Les districts Galitchski et Soligalitchski ont donné naissance à nombreux charpentiers talentueux.

En 1955, au moment où l’on se préparait à remplir les réservoirs d’eau de la centrale hydroélectrique de Gorki, on créât le musée: il fallut transférer de ces régions l’église de la Transfiguration du village de Spass-Vejy, un des meilleurs monuments de la charpente russe. Parallèlement, un groupe de bains fut transféré du village de Jarki.

Le territoire principal du musée est hors des murs du monastère. L’église de la Cathédrale de la Sainte-Vierge, en bois, transférée du village de Kholm (région de Galitch) présente un grand intérêt. Construite en 1552, elle est le plus ancien monument de la région de Kostroma. Ses formes parfaites témoignent d’une haute maîtrise des architectes.

Au-delà du mur sud du monastère, sur le territoire défendu par une digue, sont exposés la plupart des objets du musée, dont l’église du XVIIIe siècle transférée du village de Fominskoïé (région de Kostroma). Cette église est très typique; elle possède un clocher bâti sur le réfectoire. Un petit clocher de la région Tchoukhlomski, construit au tournant de chemin nous attire par sa simplicité. Erigé dans les années 60 du siècle dernier il est cependant proche quant à ses formes des anciennes constructions et nous rappelle la petite “sur les pilons de poule” izba du conte.

Sur le territoire du musée on peut trouver des izbas, des moulins et d’autres constructions en état de restauration.

Nous pouvons admirer ici des maisons aux balcons, chambranles et contrevents amusants, aux cheminées en métal et des portes ornées de dragons fabuleux et de plantes.

Il difficile de croire à l’existence, sur l’autre rive de la Kostroma, d’une grande région industrielle, d’une ville moderne.

*** (DE)In Kostroma und seiner Umgegend wurden jahrhundertelang Traditionen gepflegt, die für die gesamte russische Kultur und Kunst charakteristisch waren. Hier sind eigenartige und hochwertige Baudenkmäler, schöne Erzeugnisse der Schmiedekunst und der Holzschnitzerei erhalten geblieben.

Kostroma ist mit dem Leben vieler bekannter russischer Kulturschaffender verbunden; hier lebte z. B. der Schriftsteller A. F. Pissemski und weilten oft der Dramatiker A. N. Ostrowski, der Dichter N. A. Nekrassow, der Maler und Graphiker B. M. Kustodijew.

***Kostroma wurde in der Mitte des 12. Jh. gegründet. In jene Zeit fiel der Beginn eines aktiven Kampfes der Rus gegen die Wolga- und Kamabulgaren um den Wolgaer Handelsweg. Dieser Umstand veranlaßte die Befestigung von russischen Ansiedlungen an der Wolga; eine Festung wurde auch an Stelle des heutigen Kostroma erbaut.

In einer Legende heißt es, daß der Fürst Juri Dolgoruki, der mit seinem Heer an die Wolga gekommen war, um die Handelsleute vor räuberischen Überfällen zu schützen, ließ dort die Stadt Kostroma entstehen.

In der Mitte des 13. Jh. wurde Kostroma zur Hauptstadt eines kleinen Fürstentums, und in der ersten Hälfte des 14. Jahrhunderts vereinigte es sich mit dem Moskauer Fürstentum. Durch äußere Überfälle und feudale Kriege wurde die Stadt wiederholt niedergebrannt; deshalb sind hier keine älteren kulturellen Denkmäler erhalten. Bekannt sind nur die Ikone der Gottesmutter von Fjodorowskoje aus dem 13. Jh., die sich heute in der Kirche Woskressenje-na-Djebre befindet, und die Vitenikone des heiligen Nikolaus (jetzt im Leningrader Russischen Museum) sowie einige Kleinplastiken, die bei archeologischen Ausgrabungen auf dem Stadtgebiet gefunden worden sind. Aber auch diese wenigen Raritäten berechtigen zur Schlußfolgerung, daß bereits damals Kostroma über begabte Meister verfügte, die hohe künstlerische Traditionen geschaffen hatten, welche in der Folgezeit gepflegt und weiterentwickelt wurden.

Das auf einer wichtigen Handelsstraße des 15.—16. Jh. gelegene Kostroma entwickelte sich zu einem bedeutenden Gewerbe- und Handelszentrum und wurde am Ende des 16. und in der ersten Hälfte des 17. Jh. zu einer der größten russischen Städte.

Die von Wäldern umgebene Stadt wurde aus Holz gebaut und oft von Großfeuern heimgesucht. Nach der Feuersbrunst von 1413 wurde der Kostromaer Kreml an einem anderen, höher gelegenen Ort am Wolgaufer errichtet. Erhalten geblieben ist eine genaue Beschreibung dieses Kreml, der vierzehn Kampf türme und drei Festungstore besaß. Die Bohlenmauern wurden von einem Graben umgeben.

Heute läßt sich das frühere Stadtbild von Kostroma kaum rekonstruieren. Recht seltene Manuskripte und Zeichnungen des 17. Jh. geben uns Aufschluß über eine aus Holz gebaute Stadt mit zahlreichen Zeltdach- und Viereckkirchen, dicht aneinander gelegenen Häusern, reliefgebundenen Straßen und kleinen Holzbrücken über Bäche und Schluchten.

In der Mitte des 17. Jh. gewann Kostroma neben seiner wirtschaftlichen Rolle im Moskauer Staat auch als ein Zentrum des künstlerischen Schaffens an Bedeutung. Besonders bekannt wurden Baumeister, Ikonenmaler, Gerber, Schmiede, Silberschmiede und Leinweber. Das Kostromaer Leder wurde ausgeführt. Beliebtheit erhielten auch Rohleinen, Waagen und Schlösser aus Kostroma. Kostromaer Bauleute und Steinmetze wurden gern am Bau von Palästen und Kathedralen in Moskau und anderen russischen Städten eingesetzt.

Besonders bekannt waren Kostromaer Freskenmaler, die sich durch großartige Ausmalungen von Kathedralenwänden in Moskau und Jaroslawl, Pereslawl-Salesski und Susdal hervortaten.

Aus dem 17. Jh. stammen solche bekannte Baudenkmäler von Kostroma wie die Troiza-Kathedrale im Ipatij-Kloster, die Kirche Wos-kressenije-na-Djebre, die Ioann-Bogoslow-Kirche im Stadtteil Ipatjewskaja (heute Trudowaja) Sloboda, die Ilias- und die Spas-Preobrashenije-Kirche jenseits der Wolga und die Wosnessenije-Kirche in der Melnitschny-Gasse.

1778 wurde Kostroma zur Hauptstadt eines großen Gouvernements. In diesem Zusammenhang begann man in der Stadt mit dem Bau von neuen Amtsgebäuden.

Die Bautätigkeit wurde nach dem 1784 beschlossenen Generalplan geführt. Die wohldurchdachte Stadtplanung sowie der Umstand, daß bei der riesigen Feuersbrunst von 1773 die ganze innere Stadt niedergebrannt war, trugen mit dazu bei, daß die Vorhaben von Urhebern des neuen Entwurfs fast völlig verwirklicht wurden.

Das neue Ensemble der Stadtmitte entstand im Laufe eines halben Jahrhunderts; an ihrer Bebauung nahmen verschiedene Architekten teil. Die bekanntesten unter ihnen waren der Baumeister und -Unternehmer S. Worotilow, dessen Schaffen in das Ende des 18. Jh. fällt, und der Gouvernementsarchitekt P. Fursow, der diesen Posten in den Jahren 1822—1831 bekleidete.

***Eines der interessantesten Besichtigungsobjekte in Kostroma ist das Geschichts-und Baukunstmuseum im Ipatij-Kloster.

Im 13. Jh. als eine Festung am Zusammenfluß der Kostroma und der Wolga entstanden, stellt das Kloster ein kompliziertes Bauensemble dar, in dem Bauwerke aus dem Ende des 16. bis zum letzten Viertel des 19. Jh. erhalten sind.

Im 16. Jh. rückte das Ipatij-Kloster dank reichen Gaben, im besonderen seitens des Adelsgeschlechts Godunow, zu den größten kirchlichen Feudalherren auf. Anfang des 17. Jahrhunderts nahm die neue Zarendynastie Romanow das Kloster unter ihre Fittiche.

In der Sakristei des Klosters wurden wertvolle Kunstschätze aufbewahrt. Die Kosterbibliothek besaß unikale Handschriften und Wiegendrucke, darunter die bekannte Ipatjewskaja-Chronik — eine Abschriff der “Erzählung von den vergangenen Jahren”, eines der ältesten schriftlichen Quellen der Kiewer Rus des 9.—12. Jh.

Der älteste Teil des Klosters ist die Altstadt, die seit seiner Gründung besteht. Am Ende des 16. Jh. wurden die ursprünglichen Holzwände durch die Steinmauern mit Türmen ersetzt und im 17. Jh. überbaut. In den 40er Jahren des 17. Jh. gliederte sich an die Westmauer der Altstadt die sogenannte Neustadt an.

Längs der Mauern zogen sich Gräben, die im 18. Jh. nachdem das Kloster seine Bedeutung als Festung bereits eingebüßt hatte, zugeschüttet vurden.

Den Mittelpunkt des Ensembles bildet die Troiza-Kathedrale. Das erste steinerne Kathedralgebäude war 1558 entstanden. Es hatte Anfang 1649 infolge einer Explosion stark gelitten und wurde 1652 wiederhergestellt.

Ein großartiges Denkmal der alten Kunst ist die Wandmalerei der Kathedrale, ausgeführt 1685 von Kostromaer Ikonenmalern unter der Leitung der bekannten Monumentalmaler des 17. Jahrhunderts Guri Nikitin und Sila Sawin. Die Fresken der Troiza-Kathedrale im Ipatij-Kloster sind eines der besten Werke dieser Meister. Die Bilder sind farbenreich, sie zeichnen sich durch eine feine und sichere Linienführung aus; die Komposition weist zahlreiche genrehafte Details auf, und die dargestellten Personen sind realistisch auf gef aßt. Interessant sind die architektonischen Details in der malerischen Wiedergabe von Palästen und anderen'Bauwerken. Die Kunstmaler hatten gleichsam ein langes Leben ihrer Schöpfung vorgesehen, indem sie diese mit folgender Aufschrift versehen hatten: “Zum Betrachten und geistigen Vergnügen für alle auf ewige Zeiten, amen!”

Den fünfreihigen vergoldeten Ikonostas, ein Muster der Kunst des 18. Jh., erhielt die Kathedrale in den Jahren 1756—1758. Er wurde von Holzschneidern aus der Ortschaft Bolschije Soli ausgeführt, die damals dem Gouvernement Kostroma angehörte. Die Arbeit leiteten die Meister Pjotr Solotarjow und Makar Bykow. Besonders wertvoll sind die Ikonen der drei oberen Reihen.

Westlich von der Kathedrale, am Hauptplatz, steht der Glockenturm. Im 17. Jh. besaß er 19 große und kleine Glocken sowie eine Spieluhr. 1852 wurden die Holztreppen des Glockenturms durch Treppen aus Stein ersetzt und manche Rundbögen der Südfasade zugemauert; an der Westseite wurde eine Galerie angebaut.

Längs der Klostermauern lagen verschiedene Wirtschafts- und Wohngebäude, darunter das schlichte Dormitorium und der imposante Erzpriesterliche Palast. Das letztgenannte Gebäude wurde infolge der Launen von Erzpriestern und Baukunstmode mehrmals umgebaut.

An den Klostermauern entsteht heute ein Freilichtmuseum der volkstümlichen Holzbaukunst. Sein Ziel ist die Aufbewahrung und Exposition einzelner eigenartiger ziviler und sakraler Bauten, die die alte Architektur sowie die frühere Lebensweise in den Dörfern um Kostroma charakterisieren. Die Kostromaer Zimmerleute waren seit altersher durch ihre Meisterschaft bekannt. Besonders viele Holzgewerbtätige gab es in den dichtbewaldeten Landkreisen Galitsch und Soligalitsch.

Die Gründung des Museums datiert aus dem Jahre 1955, als der Stausee des Wasserkraftwerks Gorki gefüllt werden sollte. Aus der zu überschwemmenden Ortschaft sollte ein wertvolles Denkmal der russischen Holzbaukunst des 17. Jh. die Preobrashenije-Kirche aus dem Dorf Spas-Weshi, entfernt werden. Gleichzeitig wurden auch mehrere alte Badehäuser aus dem Dorf Sharki nach Kostroma gebracht.

Das Freilichtmuseum liegt größtenteils innerhalb des Klosters. Hier ist ein sehr interessantes Bauwerk ausgestellt — die hölzerne Bogorodiza-Kathedralkirche aus dem Dorf Cholm. Sie stammt aus dem Jahre 1552 und ist somit das älteste Gebäude im Gebiet Kostroma. Ihre kompositioneile und bauliche Lösung zeugt von großartigem Können ihrer Erbauer.

Hinter der Südmauer des Klosters, durch einen Wehrdamm geschützt, befinden sich die meisten Museumsobjekte. Man sieht hier unter anderem eine Kirche des 18. Jh. aus dem Dorf Fominskoje. Sie stellt ein Gotteshaus mit einem Glockenturm über dem Refektorium dar; zu dieser Baukomposition gehört auch eine durch ihre Schlichtheit auffallende Kapelle aus dem Rayon Tschuchloma an. Sie stammt aus den 60er Jahren des 19. Jh., ist aber ihrer Architektur nach den älteren Bauwerken nah und erinnert an das “Häuschen auf Hühnerbeinen” aus der russischen Märchenwelt.

Im Freilichtmuseum sind auch noch in Restauration befindliche Bauernhütten, Mühlen und andere Bauwerke zu sehen. Hier sind Häuser mit pittoresken Balkons, Fenstereinfassungen, Fensterläden und eisernen Ofenrohren und mit märchenhaften Drachen und wunderbaren Blumen aus Schmiedeeisen verzierten Toren.

Und man kann hier nur schwer vorstellen, daß jenseits der Kostroma eine große moderne Industriestadt mit ihrem regen Leben liegt.

K. Torop информация от «Костромаиздат» на сайте:

• «Костромичи – взгляд через столетие» первый том исторического фотоальманаха.

• Поскольку мы издаем эти книги, то становимся свидетелями этой истории.

краеведческие публикации:History and culture Kostroma region